Coaching and the Pandemic

COACHING AND THE PANDEMIC

Keri Phillips

Introductory Story

I was visiting Manchester and, whilst walking along King Street, took a spur-of-the-moment decision to visit the recently opened George Thornton Art Gallery. I should also add that calling into art galleries is a rare event for me. However, on this occasion, because I had been getting lost in the early drafting of this paper I thought I would go somewhere a bit different, but without any particular hopes or expectations.

I had a really interesting conversation with the person responsible for greeting visitors, Desiree Estrada Pinero. She is a jewellery designer who also works at the Manchester Craft Centre. We discussed creativity and she said that during the lockdown she had found it very difficult to produce anything. She profoundly missed her routine of getting out, catching up with friends over a cup of coffee. She also said that this was in contrast to some of her other artistic colleagues who had thrived during that time, being highly productive, some even more so than before.

I then went downstairs to the rest of the gallery. I was particularly struck by this picture, entitled Thou Art in Heaven:

It seemed to capture one of the key themes which, for me, had been evident in response to the pandemic; namely the reassessing of what had previously been fundamental truths. When I went back upstairs I began again talking to the jewellery designer, including my reaction to the picture. At the back of my mind the idea of including the picture in this paper began to form, along with wondering how to get permission from the artist, Matthew Leak. At that moment, the artist himself walked into the gallery and the three of us spoke briefly together about the impact of the pandemic. As I was preparing to leave I asked for his permission regarding including the picture in this paper and he happily agreed.

In reflecting on my visit, it seemed to embody some of the points which I had been planning to convey in the paper. First, as already mentioned, this is a time which has for many triggered a reassessment of some important and on occasion fundamental truths. I am also aware that there may well be many others who would see the picture in a totally different light. Recalling the moment I first saw it, it was almost with a sense of relief that I felt that the meaning had leapt out at me. Desperation for meaning might be another sign of these times. Also Philip Stokoe suggests that in times of massive anxiety we are particularly vulnerable tofalse meaning (Stokoe, 2021). It may become more important than the truth, however defined.

Certainly the search for meaning can be fundamental when grieving the loss of a loved one. ‘In the aftermath of life-altering loss, the bereaved are commonly precipitated into a search for meaning at all levels that range from the practical (How did my loved one die?) through to the relational (Who am I now that I am no longer a spouse?) to the spiritual and existential (Why did God allow this to happen?). How - and whether - we engage these questions and resolve or simply stop asking them shapes how we accommodate the loss and who we become in the light of it’ (Neimeyer and Sands, 2022: 11). Similar questions, though with less intensity may be raised regarding other losses which do not involve bereavement but are nevertheless intimate. ‘…….we ‘hold’ beliefs, and letting go of a belief is painful, it is a loss’ (Stokoe, 2021: 50).

Also my conversation with the jewellery designer regarding the highly variable impact of the pandemic on people’s creativity was a powerful reminder that there has been some ‘good news’ as well as profound challenges and pain. I have therefore sought to bring such balance to the points I later make.

My concluding reflection at this stage on my spontaneous visit to the gallery is that it was entirely a ‘gift from the universe’. As mentioned, I had already started the early drafting of the paper, but I then went into limbo. I was not sure when, whether or how to proceed. My chance visit to the gallery helped me move forward.

Introduction

In this paper I consider first the impact that the pandemic may be having in terms of the broad themes that emerge in coaching. I then narrow the focus to consider in more detail how this might play out in the coaching room and what this might mean for the coach and supervisor. I conclude by touching on the wider context and the ebb and flow of boundaries regarding coaching and the coaching profession and other stakeholders.

Themes

Less Transitional Space

For some there is less time to land into and out of ‘roles’. A classic example would be somebody engaged in child care at home who then has to move immediately into a Zoom call staff meeting; or the person who used to value their commute to work because it gave them the opportunity to prepare for winding into and out of roles and identities, whilst also having the opportunity to visit their favourite café.

In this regard it is worth noting that transitional space was an important aspect of Donald Winnicott’s work on child development: an opportunity for the child to begin to distinguish between itself and its mother, between its inner and outer worlds, perhaps whilst hugging Teddy, the transitional object (Winnicott, 2005). The child is just starting to learn not only that Mother is a separate being, but that maybe he or she can survive without her. In the adult, it is a time where there can be reflection and hence aligning thoughts, feelings and behaviours in order to manage oneself in and through different worlds. This might also be a time for learning, ‘I’ll step in a bit more at the next staff meeting’.

I realise that some have thrived through not having to travel. This also includes those who have developed new business opportunities. Also I know that some coaching and therapy clients feel safer and are more open when talking on Zoom, rather than meeting face-to-face.

The loss of transitional space might also mean that one does not feel safe enough to be uncertain. Ambivalence is an important part of learning and allowing truths to emerge; for example, that one can want both to be heard and to be one of the herd. If one does not feel safe enough to be uncertain there can, for example, be an urge to join a group simply to belong, whilst pushing aside one’s sense of unease. Having done so one may then be inducted into a world where one has to ‘toe the line’; this sometimes extending to the condemnation of others and even tribalism (Phillips, 2020). Those who are apparently lukewarm members may be despised even more than the other ‘tribe’ (Alderdice, 2021).

There might be a more ‘civilised’ and polite form of tribalism where people retreat to their specialism as a place of presumed safety. They can reinforce the armoury of their perspective to the point where they fail to reach out with an open hand.

Being in a transition where there is space gives one, as mentioned, an opportunity to move between identities, and there may be scope for personal development such as becoming a stranger to oneself. Rather like Sigmund Freud’s reference to das Unheimlich; the weird: unexpectedly catching a glimpse of one’s reflection in a shop window, ‘Who’s that strange looking old bloke…….OMG, it’s me!’; strange, but familiar. That might also be another meaning in the Thou Art in Heaven Picture. Potentially, a ‘loving dislocation’ which may prompt reflection and insight (Phillips, 2019).

For example, I remember recently visiting London and being disorientated by the lack of traffic, especially along The Strand and Whitehall. In stepping back, both literally and metaphorically I was suddenly filled with many memories of my first job, as an eighteen year old, working in The Old War Office Library. In then walking around this so familiar yet different area, it led me to consider what currently excites me more and less in my current work.

I am also reminded of Halina Brunning and Olya Khaleelee writing about our currently living in a time of disappearing containers. ‘…… survival is contingent on a reliance on an emotional container of some kind that will provide a ‘holding’ function’ (Brunning and Khaleelee, 2021: 37). The container needs to be neither too loose nor too tight. A space to explore, whilst being reasonably safe, just like the child with Teddy. Equally a space where one can begin to grieve.

Brunning and Khaleelee’s reference to ‘survival’ leads me to my next point.

Concern about Survival

Survival in the broadest sense of the word has become more and more vivid as an issue. This ranging across a large spectrum from the loss of a loved one, through to business decline or disintegration, political upheaval and on to global warming; perhaps even various combinations of these. Many feelings may flow from this, often interwoven- anger, guilt, relief, sadness, fear, love, despair, frustration, excitement….these perhaps changing moment to moment.

One of the challenges for the client, coach and supervisor is that the shared intensity of these collective existential issues may make it more difficult to balance being both a part of and apart from each other. For example, the helper’s (coach/supervisor) self-protection mechanism – perhaps visceral and originating in childhood – may come to the fore, even though she had previously considered it worked through. For example, the helper might become a bit too theoretical in order to avoid the intensity of emotions or find other ways of being subtly elusive, both with the client and with self. The coach supervisor might spend more time embodying the archetype of the Teacher, rather than the Guardian or Healer, because it feels like a sanctuary to her (Phillips, 2019).

Equally, in response the client’s self-protection mechanism may be activated, experiencing the helper as distancing herself in some way. The client’s sense of being betrayed, perhaps yet again in life maybe just when he had decided, because of the turbulent environment to bring rather more personal and intimate concerns into the coaching room. Quite possibly neither party feels sufficiently ‘held’ and there may even be an element of regression which, in the language of transactional analysis, ends up reinforcing early script decisions (Steiner, 1975).

Survival may be linked to a sense of vulnerability. In a world of turbulence that which seemed ‘under control’ can suddenly become elusive or indeed dominant or oppressive. One mundane and obvious example would be the mobile phone. It could be that, head down, one loses contact with the nourishing and exciting potential of one’s environment. I am reminded of Rebecca Solnit’s brilliant book, ‘Wanderlust’ and her reference to the filling up of ‘time in between’ (Solnit, 2014: xiii). It may even simply mean not paying enough attention to the safety of oneself or others. Certainly I vividly recall seeing a man near Woburn Place, Euston, London, who walked straight into the road whilst on his phone and knocked over a cyclist who narrowly missed being run over by a double-decker bus.

I want to stress that a sense of vulnerability can be valuable in prompting curiosity and learning (Phillips, 2015). This links with Babette Rothschild writing in the context of trauma treatment that it can be important to keep a defence mechanism as an option; it is about adding to choices and extending one’s repertoire (Rothschild, 2021). The client may decide that it can sometimes be helpful for self and indeed others to avoid being the truth teller; perhaps also, to be less open about oneself. Vulnerability can enhance insight. It is about balance, whilst also accepting that losing one’s balance is an important strand in learning.

Vulnerability may also prompt creativity and the urge to be adventurous. This may be linked to a sense of survival which brings legacy to the fore. One may have a sense of having survived despite being ‘wounded’ – the origin of the word vulnerable – and one has the urge to create and leave something for the next generation, whether one’s own family or more widely.

Another dimension regarding the current world environment is the internet. That which was hoped by many to be a tool enabling humankind to be omniscient and omnipotent has in many ways turned us into mere data material, ripe for exploitation, quite possibly in ways we know nothing about (Zuboff, 2019). During the pandemic it has become even more central to many lives. Also where there is a failure of the internet, whether due to outage, political interference, sabotage, incompetence or technical failure, the consequences can be profound, with the pendulum swing causing us to feel ignorant and impotent; hopes raised and dashed and raised and dashed again, as a matter of routine.

This is compounded by the actual content where, for example, the social media love turns out to be exploitation, bullying or hatred; and the fake news may not be uncovered: existential betrayal. A betrayal in the present which may sometimes, as indicated in the next section, have reverberations with betrayal in the past.

Where one’s world is being experienced as turned upside down it is often a challenge to find even some temporary solid ground. This is potentially true for both the helper and helped, including of course the supervisor. Solid ground is needed but where does one stand in order to find it?

Intergenerational Trauma

Profound challenges to one’s sense of survival can activate the pain of the past and that which has been endured in previous generations. One did not have these experiences oneself, but they are part of one’s being: postmemory. ‘The post memory of war may be printed into our DNA as well as printed in books’ (Green, 2021: xviii). Perhaps there are tragic or terrifying experiences about which one does not wish to talk. One of the consequences might include children not being taught their mother tongue (Zarbafi and Wilson, 2021). This then leads to a sense of ‘something missing’ or untold which might be carried through the following generations. The clear even tangible story is ‘lost’, but the associated feelings are still vibrant viscerally even if they cannot be articulated. This has parallels with the distinction Sigmund Freud made between melancholia and mourning; the former being a vague yet intense sense of something or someone that one loved having been lost; the latter having greater clarity about the loss and consequently there is the possibility of some degree of closure, for example being able to say au revoir. There might have been a lack of time for mourning, no transitional space.

In the setting of organisational change sometimes staff are discouraged from looking back, acknowledging and celebrating the past; any nostalgia is treated as potentially a lack of commitment to the present and future. This stifling of the opportunity to mourn may mean that staff are more likely to hold onto the past as the golden era (Visholm, 2021). A vicious circle is created because that which is forbidden becomes ever more seductive.

Rony Alfandary refers to the experience of never feeling quite feeling at home, although one is home (Alfandary, 2021). This strand can potentially be linked to colonialism and the complete uprooting, in every sense of the word, to another place, culture and the destruction of one’s physical, emotional and spiritual home. Samuel Kimbles writes, ‘We in America have long lived with the ongoing reality of a history of slavery that has not been emotionally worked with and engaged. This history continues to haunt our family’ (Kimbles, 2021: 31). Perhaps this denial and the associated polarisation were part of the emotions which, along with other factors, energised the 6th January attack on the Capitol?

Some, such as Alice Miller, suggest that forgiveness does not resolve hatred but simply causes the trauma to be passed on to the next generation (Passalaqua and Puricelli, 2021). This may particularly be the case if the legacy of forgiveness is passed on from a position of ‘ought’ rather than ‘want’; ‘you ought to forgive’. Through the generations it then becomes particularly difficult to tell the difference between ‘ought’ and ‘want’ because it has become part of one’s being, even though in a corner of one’s soul there may be occasional glimmerings of ‘something is not quite right’.

Following on the point about being taken from home, I am reminded of Esti Rimmer writing that ‘exile’ is experienced as a forceful removal, an unnatural interruption of the connectedness between a specific time and place. She sees it as a traumatic event disrupting stable child development (Rimmer, 2021). Major disruption in the present, such as the pandemic may provoke disruptive memories and experiences from the recent and distant past, both one’s own and previous generations. This involves different ‘ages’, in both senses of the word.

On the other hand, moving between cultures, whether through choice or not, may ultimately lead some people to develop a versatility which enables them to move relatively smoothly through a wide range of contrasting circumstances. This, including the ability to step back and consider, ‘What is appropriate for me here?’. One learns to take the 3rd position, being an observer of oneself and one’s situation.

I am also reminded that sometimes somebody can firmly believe that their true home lies somewhere else, which they left many years before. However, when eventually they ‘go home’ it is no longer the place which they recalled as having nourished them. It is different, becoming strange, even alien, whether through the tangible, such as building development, or there simply being a different ‘atmosphere’. ‘It doesn’t feel the same’. It is no longer the nurturing transitional space it once was. Perhaps it is self that has changed rather than the location. Holding the dream about the past may have been important. Now it is no longer needed.

This theme also links to the fact that some organisations seek to create the culture and atmosphere of a family. If subsequently, for whatever reason the employee is made redundant at some point he may then feel profoundly rejected, whatever the reason and no matter how ‘logical’. There may then be echoes of rejection from previous families, whether real, imagined or a mixture; parental betrayal. Indeed he may have joined the organisation in the first place because it had the apparent culture of a loving family, but he was mistaken. ‘On the one hand, companies are less loyal than ever, and on the other hand they demand a stronger emotional commitment’ (Visholm, 2021: 172). Equally, as Philip Stokoe writes, ‘In the role of leader there is the constant danger of being caught in a requirement to be omnipotent and omniscient. The danger for the incumbent is an unconscious belief that leaders ought to have all the answers’ (Stokoe, 2021: 199). They may end up trying to be the ‘container‘ for everyone and everything. Consequently they themselves do not feel sufficiently held. Intense self-protection may be triggered, including childhood habits and ways of thinking – childlike and not necessarily childish - which had been dormant for years.

In essence these themes are part of a pandemic environment which provides many opportunities and challenges. Regarding the former there is the possibility of engaging with those from totally different backgrounds and approaching broadly the same issue through fresh eyes. Regarding the latter there is potentially a downward, destructive spiral where turbulence creates uncertainty and a huge urge to ‘be in control’ and this itself then provokes division which gives added impetus to the turbulence. Being able to step back, to take the 3rd position becomes even more necessary and potentially more difficult.

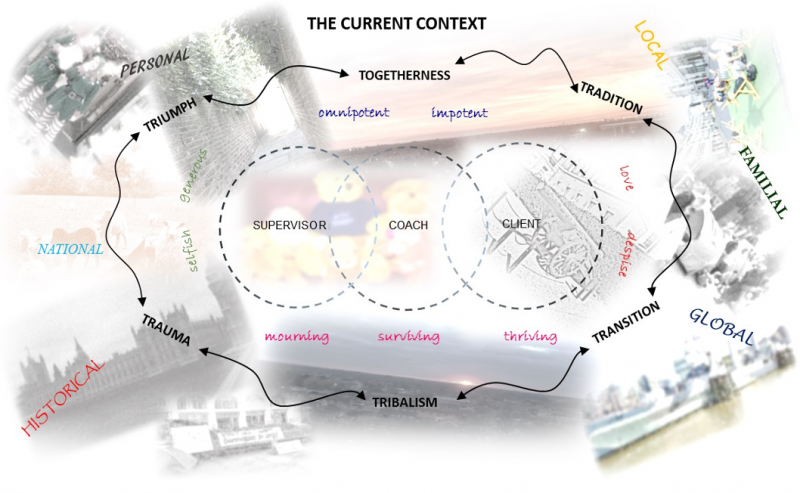

An overview of the points above is covered in the diagram which follows:

The Possible Consequences

Clearly, as a result of the themes above many varying issues might arise in the coaching room. Some examples could be: compassion fatigue, indifference and a loss of curiosity, feeling powerless, making everything personal, feeling like an outsider having been an insider, lack of self-care, loss of self, a sense of betrayal, feeling angry and sad for much of the time and lastly, carrying the burden of being a representative. As an example of this final point I cite the work of Ibram Kendi. He refers to Black people often being harshly judged by other Black people because if they make a mistake they are regarded as letting down the whole race. This is in contrast to White people who are allowed to be individuals with faults (Kendi, 2019; see also, Roche and Passmore, 2021).

Such issues as those above may or may not be openly discussed in the coaching; they may emerge over time or simply ‘have a presence’, but are not explicitly considered; an untold story. Boundaries are clearly important under these circumstances. However some boundaries may have changed during the pandemic and I illustrate this below by offering two models indicating broadly how the psychodynamics may have shifted for some clients.

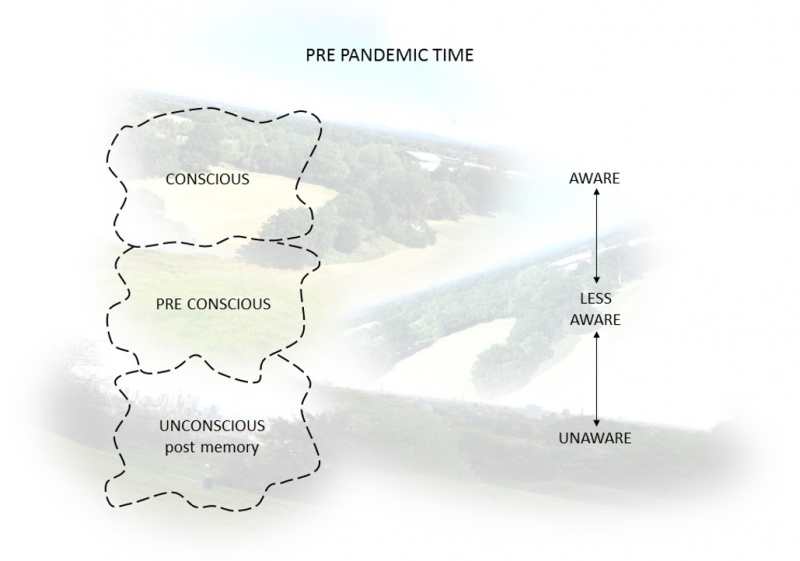

The idea of three levels of awareness originated in the world of psychoanalysis, but I am using them without all the Freudian layers – id, ego and superego (Jarvis, 2005) - whilst also adding postmemory which links to my earlier model including tradition, trauma, togetherness, tribalism and triumph and transition.

Conscious – e.g. the client fully and immediately recognising that he needs to speak his mind more at meetings. Indeed that might be the explicit reason that he came to coaching in the first place.

Preconscious – e.g. after a number of sessions he gradually begins to recognise that he tends to ‘undersell himself’ in many different situations, both work and personal.

Unconscious – e.g. he eventually realises that when he was a boy part of him hated as well as loved his elder sister. She was the clever, funny and talkative one who seemed always to be the centre of attention whenever they were together. He tended to be ignored…..at least he felt he was. Sitting quietly at the back seemed the best and safest place to be.

Post memory - Generations brought up in the Welsh Valleys. A strong sense of community but with high standards and quick judgements. The Depression of the 1930’s had a profound effect raising concerns about survival and whether to leave or not. Will it be possible to make a home elsewhere? What will be the personal price?

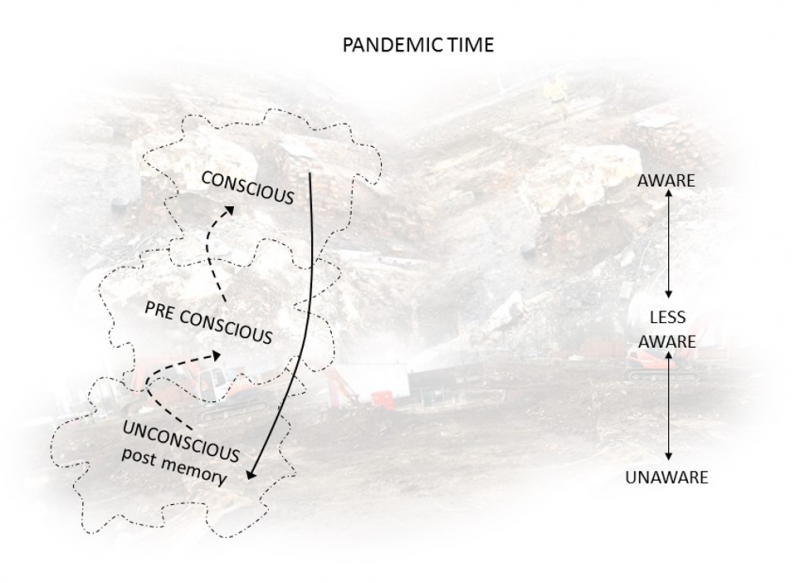

I suggest that for some clients, in the light of the pandemic, their world is more like this, particularly if they have a sense of upheaval:

The boundaries have an increased fluidity and permeability whilst one also feels somewhat off balance.

There are a number of possibilities flowing from this including:

- The unconscious and postmemory may move to slightly greater awareness, though not necessarily with any particular or clear memory; just a vague and intangible sense of something new being present.

- That which had been preconscious and at most vague glimmerings suddenly bursting onto the scene and being vividly present and demanding attention. “I know now that this job is truly not for me! I must get out!”. This might include breaking down myths and consequently a catapult back to the past and the time and age when the myth was first absorbed into one’s being. The timeline collapses (Alderdice, 2021).

- That which had been conscious, now suddenly being pushed down, inside or outside awareness. It may become ‘armoured’ and a totally no-go area. Perhaps a sense of profound loneliness and a belief that exploring it would be too painful.

Clearly any of the above might have also happened in prepandemic times. My suggestion is that these possibilities are more likely as a result of the pandemic. The disturbance of internal boundaries reverberating with the disturbance of external boundaries and vice-versa. This may make trust, both in oneself and others even more important yet more elusive.

Such potential dynamics mean that it becomes even more important that the coaches pay attention to the boundaries of their work to ensure they ‘do no harm’. The potentially shared existential dimension referred to earlier in the paper means that the coach’s boundaries may be challenged similarly to, even intimately like the client’s. The coach needs to be held and hold self sufficiently in order to hold the client. This also applies to the supervisor and the supervisor of the supervisor.

Some possible actions the coach might take include:

- Reviewing habits that might have become unhelpful in some way. Most, if not all coaches will have their favourite methods, philosophy and ways of being. Perhaps these have become a ‘container’ which is a bit too tight for self and others in the current environment. This might have happened gradually, without awareness.

- Seeking other perspectives, including outside one’s habitual circle of colleagues. Colleagues may be in the same container, possibly even with strands of ‘groupthink’; this may be due to having a shared specialism. Specialisation can bring depth but, as suggested earlier in the paper, this may be at the expense of vital width. There may have been insufficient questioning of assumptions, let alone the assumptions about assumptions (Argyris and Schon, 1978). The increasing globalisation of coaching creates ever more opportunities for learning across cultures and diversities.

- Considering whether one feels ‘held’ enough by one’s colleagues and sufficiently supported. Perhaps the support was sufficient for the pre pandemic times, but the extra demands of the present may mean that more is needed. ‘Compassion fatigue is identical to secondary traumatic stress and has to do with the nature of helping professional work. This emotional state can emerge suddenly, without much warning, and carries with it a sense of helplessness, confusion and isolation’ (Morrissette, 2022: 145).

- Checking whether sufficient resources and contacts are in place to support those who may have mental health issues; for example, the diagnosis and possible referral.

- Being alert to the possible need to recontract; perhaps making this a routine in all aspects including aims, code of ethics and administration. Bringing a ‘fresh start’ perspective, from time to time.

- Noticing whether one might have deified a guru because of one’s hunger for meaning and certainty. I am also reminded of a phase in the history of psychoanalysis when claims of child abuse were dismissed as fantasy. ‘Generations of women and men seeking treatment for the impact of actual childhood abuse were further traumatised when told by their clinicians that the abuse never occurred but was instead wished for and fantasised, in many ways replicating and tragically exacerbating what these children had been told by parents and other adults unable to accept the horrific truths their children dared to report’ (Kuchuck, 2021: 84).

- Noticing whether one is too keen to make meaning for the client. Meaning which one desperately wants for oneself. This could prompt giving coherence to a client’s story which it does not have, including linking it to one’s favourite theory.

- Considering whether one’s coaching team colleagues, perhaps in response to a beleaguered and exhausting environment where warmth is in short supply have developed an environment which is insufficiently challenging. The love and warmth in the team are welcome, perhaps vital, but it may also mean that the probing of each other’s principles and practice has been blunted. Incisiveness has been collectively reframed as lack of empathy, perhaps unwittingly so.

- Checking whether mourning and saying good-bye – to people, places, beliefs – are being given sufficient attention. This may require a fleeting moment through to a ritual.

- Supporting one’s curiosity and creativity in a variety of ways. For example, one might habitually be a pilgrim, having a particular destination in mind. One might instead experiment with being a meanderer, or even a flâneur. For some, being a tourist might be an engaging mid-way point (inspired by Solnit; see also Patterson, 2019).

As mentioned earlier, boundaries is clearly an important theme. I was valuably reminded of this recently at a workshop where Natalia de Estevan-Ubeda and Peter Duffell were describing their excellent and much needed research into the relationship between mental health and coaching and supervision and they mentioned the multiplicity of boundaries, including blurring ones (de Estevan-Ubeda and Duffell, 2021).

Also Neil Scotton and his colleagues have, with Neil’s Wheel, inspired the development of an ever-widening global coaching community. This has focussed on enabling conversations which support participants in aligning who they truly are with what they want to achieve. For many this has meant a particular focus on the protection of the natural environment (Scotton, 2020).

Environmental justice requires social justice.

This leads me to the conclusion of this paper.

Desiree Estrada Pinero

A blue gargantilla choker. It represents the sea, a place of escape and home in Caracas.

A blue gargantilla choker. It represents the sea, a place of escape and home in Caracas.

Conclusion

During this century coaching has evolved and expanded in many different directions and continues to do so. This has ranged from the methods and technology used through to the philosophies and backgrounds of those involved, through to a growing global number of stakeholders: accrediting bodies, coach and supervisor training institutions, national bodies, organisation development consultancies, sole traders and many other people and establishments, big and small, which have involvement with coaching and supervision.

These cultural, collective and specialist boundaries are evolving, ebbing and flowing and overlapping…..and blurring. All this quite possibly accelerated by the pandemic. Just one of many examples would be the rising number of those with mental health issues and the ways in which the coaching profession could and should respond. The identity and purpose of the stakeholders is evolving just as it often is for the individual client in the coaching room. So, just as balancing being a part of and apart from is important on a 1:1 basis in the coaching room, equally such a balance is necessary systemically. Hence there is the possibility in any of these settings, local or global, of insightful support based on self-reflection and the shared journey, through to an unwitting sabotage brought about as a result of bringing too much of one’s own unfinished business to one’s coaching work.

One of the challenges in the world at present is about balancing collaboration and competition. This has been evident through the creation and distribution of vaccines. Gita Gopinath, the chief economist of the International Monetary Fund recently said, ‘The dangerous divergence in economic prospects across countries remains a major concern. These divergences are a consequence of the “great vaccine divide” (i Paper 13 October 2021). From a somewhat similar perspective Nestor Braunstein writes, ‘In principle the pandemic should be an avatar that homogenizes its inhabitants: everyone is or can be its victim but…..far from that, the disease highlights the differences of wealth and power, underscores the hegemony of the few over the many and makes evident the latent violence present in the social under capitalism. We are not “all in the same boat” as it was originally presumed’ (Braunstein, 2021: 113). Similarly climate change has been a greater threat to the poorer parts of the world, though recently richer countries have also been suffering some significant damage.

Consequently in these times of the pandemic and climate change there is the risk of growing divisiveness. The coaching community, as it develops in many different ways and many different places, has much to offer, particularly in helping create a balance between collaboration and competition. To do so it needs to maintain and enhance its capability to be a bridgebuilder, both internally and externally.

I spoke to Lloyd who works at the Trove Cafe in Manchester and is also a musician. I asked him what music captures for him the essence of the pandemic. He said he needed to time to think about it.

I caught up with him a few days later. He said it was Jack Garratt’s song ‘Mara’. For Lloyd the theme in it is about ‘sitting with difficult thoughts, accepting and understanding them, rather than pushing them away’. He thought this was probably a challenge faced by many during the pandemic.

References

Alfandary, R. (2022). Postmemory, Psychoanalysis and Holocaust Ghosts. The Salonica Cohen Family and Trauma Across Generations. London and New York: Routledge.

Argyris, C. and Schon, D. (1978). Organizational Learning. A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Braunstein, N. (2021). Psychoanalysis, too, will never be the same. In Castillon, F and Marchevsky, T (eds). Coronavirus, Psychoanalysis and Philosophy. Conversations on Pandemics, Politics and Society. London and New York: Routledge.

Brunning, H. and Khalelee, O. (2021). Danse Macabre and Other Stories. A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Global Dynamics. Bicester: Phoenix.

De Estevan-Ubeda, N and Duffell, P. Mental Health in Coaching and Supervision. Ready or Not? Global Supervisors Network 8-9 October 2021. (also forthcoming article in Coaching at Work).

Green, D. (2022). Foreward. In Alfandary, R. Postmemory, Psychoanalysis and Holocaust Ghosts. The Salonica Cohen Family and Trauma Across Generations. London and New York: Routledge.

Alderdice, Lord John. (2021). On the psychology of religious fundamentalism. In D. Morgan (ed). A Deeper Cut. Further Explorations of the Unconscious in Social and Political Life. Bicester: Phoenix.

Jarvis, M. (2005). Theoretical Approaches in Psychology. London and New York: Routledge.

Kendi, X. (2019). How To Be Anti-Racist. London Bodley Head.

Kimbles, S.L. (2021). Intergenerational Complexes in Analytical Psychology. The Suffering of Ghosts.London and New York: Routledge.

Kuchuck, S. (2021). The Relational Revolution in Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. London. Confer.

Morrissette, P.J. (2022). Self-Supervision. A Primer For Counsellors and Human Resource Professionals. London and New York: Routledge.

Neimeyer, R.A. and Sands, D.C. (2022).Meaning Reconstruction in Bereavement. From Principle to Practice. In Neimeyer, R.A., Harris, D.L., Winokuer, H.R. and Thornton, G.F. (eds). Grief and Bereavement in Contemporary Society. Bridging Research and Practice. London and New York: Routledge.

Passalaqua, L and Puricelli, M. (2021). Alice Miller on Family, Power and Truth. In Morgan, D. (ed.). A Deeper Cut. Further Explorations of the Unconscious in Social and Political Life. Bicester: Phoenix.

Patterson, E. (2019). Reflect to Create! The Dance of Reflection for Creative Leadership, Professional Practice and Supervision: Ingram Spark.

Phillips, K. (2015). Vulnerability, Culture and Coaching. Manchester: KPA.

Phillips, K. (2019). Working with Intense Emotions. In Turner, E. and Palmer, S. (eds). The Heart of Coaching Supervision. Working with Reflection and Self-Care. London and New York: Routledge.

Phillips, K. (2019). Haunting As Loving Dislocation. Manchester: KPA.

Phillips, K. (2020). A Perspective on Polarisation. Manchester. KPA.

Rimmer, E. (2021). Language of the mountains, language of the sea: living with exile and trauma as a journey between languages. In Zarbafi, A. and Wilson, S. Mother Tongue and Other Tongues. Narratives in Multilingual Psychotherapy. Bicester. Phoenix.

Roche, C and Passmore, J. (2021). Racial Justice, Equity and Belonging in Coaching. Henley on Thames: Henley Business School.

Rothschild, B. (2017). Revolutionizing Trauma Treatment. Stabilization, Safety, and Nervous SystemBalance. New York. Norton.

Rustin, M. (2021). The coronavirus pandemic and ins meanings. In Levine, H and de Staal, A.

Psychoanalysis and Covidian Life. Common Distress, Individual Experience. Bicester: Phoenix.

Scotton, N. (2020). Do You Care About This Too? Coaching Perspectives Magazine, November 9, 2020. Association for Coaching.

Solnit, R. (2002). Wanderlust. A History of Walking. London: Granta.

Steiner, C. (1975). Scripts People Live: Transactional Analysis of Life Scripts. New York: Grove Press.

Stokoe, P. (2021). The Curiosity Drive: Our Need for Inquisitive Thinking. Bicester: Phoenix.

Visholm, S. (2021). Family Psychodynamics in Organizational Contexts. London and New York: Routledge.

Zarbafi, A. (2021). Living in-between languages and cultures. In Zarbafi, A. and Wilson, S. Mother Tongue and Other Tongues. Narratives in Multilingual Psychotherapy. Bicester: Phoenix.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile

©Keri Phillips 2021

Contact details:

[email protected]

www.keriphillips.com

Share this article

Accredited Coaching Supervisor

Author: Christoffel Sneijders

Author: Sylviane Cannio, MCC, MP, ESIA

Author: Michelle Lucas

Online Community

Become part of our online family. Connecting and empowering each other to succeed. We want to give supervision wider exposure and a larger 'share of voice' in the coaching community. Come and join us!